Cat Health Section – FLUTD in Cats (Cystitis)

What is FLUTD?

FLUTD stands for “Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease,” and is the currently accepted veterinary term for what the rest of the world calls “Cystitis.” The naming of this condition changes quite frequently as more becomes known about the disease; FLUTD used to be called “Feline Urologic Syndrome,” or FUS.

You can see that FLUTD is a very ambiguous term, and in itself means practically nothing, except that your cat has disease somewhere in her lower urinary tract. When vets talk about “Cystitis,” they almost certainly mean FLUTD.

What are the Symptoms of FLUTD?

As you would expect, all the symptoms relate to the urinary tract. If your cat has FLUTD, she may display one or all of the following:

- Increased frequency of urination.

- Difficulty passing urine – straining in the litter tray.

- Blood stained, or discoloured urine.

- Painful urination, causing crying during urination.

- Breakdown in litter training.

The typical cat with FLUTD is one that makes frequent visits to the litter tray, passing small quantities of bloodstained urine with some difficulty, occasionally urinating on carpets or beds.

This picture shows heavily bloodstained urine from

a particularly severe case of FLUTD. The affected

cat had struvite urolithiasis (see below).

If the outflow to the bladder has blocked completely, there may be any of the following symptoms in addition to the above:

- Vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Collapse

- Death

This is a very distressing disease for all concerned, and if your cat is displaying these symptoms you should go to the vet as soon as possible, especially if he is male. Male cats can get completely blocked bladders, and are unable to pass urine. They make repeated visits to the litter tray, and strain but with no result. People often mistake this for constipation. If you have a male cat that is straining without producing any urine bring him to the surgery immediately. This is a genuine emergency.

What is the Cause of FLUTD?

Clearly, because FLUTD is such an ambiguous term, there must be many different causes. The reason that we use this name is because no matter what the underlying condition is, the symptoms are always the same. In most cases you simply cannot tell what the cause is just by looking at the cat. The different causes of FLUTD are:

- Bacterial infection

- Urolithiasis (bladder stones)

- Viral Infection

- Tumours (cancer)

- Abnormalities in the anatomy of the urinary system

- Physical injury

- Blocked urethra¹

- Idiopathic²

Note 1: The urethra is the tube that takes urine from the bladder to outside the body.

Note 2: Idiopathic means “Unknown cause.”

There are a few others, such as problems with the immune system, but the list above covers the overwhelming majority of cases.

The last in this list, idiopathic, is a bit of a cop-out. It does not mean that there is no cause, just that a cause cannot be identified.

Unfortunately, this covers about two thirds of all cases of FLUTD. It may be that a single disease entity is responsible, but we just have not worked it out yet. What is more likely though, is that there are a number of other diseases that are, as yet, waiting to be discovered.

Looking at idiopathic FLUTD, there are several lifestyle factors that we know increase the risk of a cat getting the disease. These are:

- Obesity

- Neutering

- Low water consumption

- Feeding dry cat food

- Feeding very frequently

- Lack of exercise

- Living indoors

Some of these are clearly linked. For instance, cats fed dry food have a lower overall water consumption than cats fed canned food, because canned food is 80% water, and dry food is only about 10% water. This is still true despite the fact that cats on dry food physically drink more than cats fed canned food. Cats fed exclusively on dry food tend to be more likely to be obese. In addition, cats that spend all their time indoors sleeping, or looking out of the window will take less exercise, and are more likely to become obese. The age of neutering has no effect on the propensity to develop FLUTD.

How is FLUTD Investigated?

The majority of cats with FLUTD have the idiopathic form, but it is important to properly investigate the syndrome in order to rule out the possibility of one of the other causes.

Unless the cat has a completely blocked bladder, most of the investigation can be performed on an outpatient basis in one day.

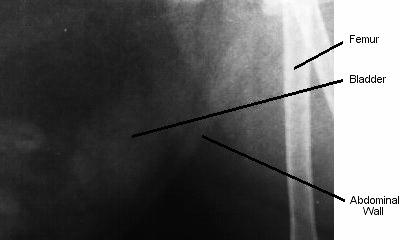

The first step is to collect urine. The preferred technique is to collect urine using a needle inserted into the bladder through the wall of the abdomen, and it is possible to do this in most cats without sedation or anaesthesia. However, it will also be necessary to x-ray the cat’s bladder, and this technique needs to be performed under general anaesthesia. Therefore, it is best to administer a general anaesthetic first, and for technical reasons, it is best to x-ray the bladder before removing any urine.

Before administering the anaesthetic, we give the cat an enema to remove faeces from the colon. This is important because the colon lies above the bladder, and if it is full of faeces, it significantly affects the interpretation of the x-ray. After administering a general anaesthetic, an x-ray picture of the bladder is taken. Some large bladder stones will be visible on this first x-ray. A urine sample can then be taken using a needle into the bladder. This urine sample is separated into two, and one sample sent for bacterial culture. The second sample is centrifuged (spun at a very high speed), and any deposit examined by a pathologist. This deposit may contain tumour cells, blood cells, bladder lining cells, or bacteria, and is a very useful indicator as to the underlying processes causing disease in the cat. A catheter is then placed into the bladder, (a catheter is just a thin plastic tube), and any remaining urine withdrawn.

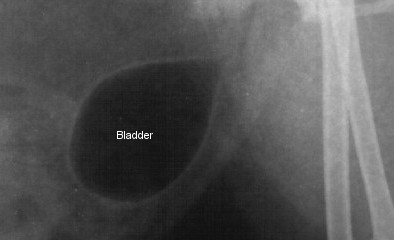

If there is a large stone visible within the bladder, it is probably not important to do this next step. After removing all the urine, air is injected into the bladder via the catheter, and a second x-ray picture taken. This is called a pneumocystogram, and allows the bladder wall itself to be seen. Without doing a pneumocystogram it is only possible to see an outline of the position of the bladder. Certain types of bladder stone are also more easily seen on a pneumocystogram. This effect is shown on the following two x-ray pictures of a cat’s bladder:

In this picture, taken with the cat on her side, with her bladder

full of urine, you can only see the area that the bladder occupies.

This is the same cat, that has had the urine removed from her bladder,

and replaced with air. You can now see the bladder wall much more clearly.

If the pneumocystogram is normal, there is no need to take further x-rays. However, if there is any doubt as to how normal the bladder wall is, a final x-ray may need to be taken, known as a double-contrast cystogram. For this, a small volume of a liquid is injected into the bladder, again via the catheter, with the air still being present within the bladder. The cat is rolled over on her back a few times so that the liquid coats the wall of the bladder, before the x-ray picture is taken. Air in the bladder allows x-rays to penetrate the cat more easily than if it were full of urine. The liquid that is used absorbs x-rays, and so make it harder for them to pass through the cat. The resulting picture gives a very good view of the lining of the bladder, and is particularly good at demonstrating the presence of a bladder tumour.

X-ray pictures will be normal in most cases of bacterial or viral infection, and in idiopathic FLUTD. However, severe bacterial cystitis can cause a marked thickening of the bladder wall, that is difficult to distinguish from bladder cancer. Therefore, x-ray images have to be judged in conjunction with the other important tests.

If all the tests are negative (and it does take a day or two for bacterial cultures), there may be nothing else for it, but to operate, and cut into the bladder to see what is happening. Suspicious areas of the bladder wall can then be biopsied, or tumours removed.

How is FLUTD Treated?

The treatment of FLUTD is determined by what exactly is causing the disease:

Bacterial Infection.

Less than 5% of cats with FLUTD have a bacterial infection of the bladder. Consequently, the routine use of antibiotics to treat FLUTD is difficult to justify. During the investigation procedure, there are two ways in which bacterial infection will become evident. The first is on the physical examination of the urine sediment, where bacteria may be visible. The second is on culture of the urine, where a laboratory attempts to grow the bacteria responsible for the infection. Where the bacteria involved is isolated, it is tested to see which antibiotics it is sensitive or resistant to. In that case, we can select the appropriate antibiotic. Treatment of bacterial infection is usually very successful.

Urolithiasis

In the cat, uroliths (bladder stones), are usually one of two types: “Struvite” or “Oxalate.” Struvite is also know as triple-phosphate. Crystals form in the urine when the concentration of a material exceeds a critical point above which more of this material cannot remain in solution. This is the same process as the way salt crystals will form in a glass of salty water as the water evaporates. However, microscopic crystals in the urine are a normal finding in many cats, and is not in itself indicative of a problem. It is only large crystals that are visible to the naked eye that are called uroliths. In female cats, quite large uroliths can pass through the urethra without causing any problems. Male cats have a much narrower, longer urethra, and this blocks much more readily than in females.

By looking at the urine sediment under a microscope, it is possible to determine what type of urolith is present by the shape of the crystals that are found in the urine. In the majority of cases, the crystals will be composed of the same material as the urolith, but just because a cat has crystals in its urine, it does not mean that they are the cause of the FLUTD.

The presence of uroliths in the bladder presents something of a dilemma to a veterinary surgeon. If the urolith is composed of struvite, it is possible to dissolve it by modifying the diet. Struvite uroliths are much more soluble in acidic urine, and by giving a diet that promotes the development of an acidic urine, while limiting the components of the urolith, then it can dissolve. Struvite is composed of magnesium, phosphate and ammonium. Ammonium is formed as a by-product of protein use, so the diets that are available to do this are typically restricted in protein, magnesium and phosphate. They may also have added sodium so encourage the cat to drink more, and so produce a more dilute urine. However, the process of dissolving uroliths can take many weeks, and about 10% of struvite uroliths are infected, and if this is the case, the cat needs to take antibiotics until four weeks after all the uroliths have been dissolved. It typically takes up to two months for all the uroliths to dissolve, so the cat will be on antibiotics for up to thirteen weeks.

Failure of the urolith to dissolve is quite possible, and this can be for a number of reasons. For instance, there may have been a misdiagnosis as to the type of urolith that is present. Probably more common is poor compliance with the diet. Some cats are prolific hunters, their owners blissfully unaware of the situation. Others spend their day travelling around the neighbours’ houses, being fed at each place, or stealing food left out for other cats.

Calcium oxalate uroliths cannot be dissolved by changing the diet, and where these are present, they must to be removed surgically. It appears that the diets that are commonly used to prevent struvite from forming actually increase the likelihood of calcium oxalate uroliths being produced. Diets that are used to prevent struvite have reduced magnesium, increased sodium, and promote the formation of acidic urine. All three of these factors favour the development of oxalate uroliths, so in treating one problem, we can create another. As the awareness of the importance of magnesium levels in the diet and its role in the formation of struvite has increased, so the incidence of struvite uroliths has decreased and oxalate uroliths increased. Oxalate uroliths can also form in the kidneys and ureters, (the ureters are narrow muscular tubes that take urine from the kidneys to the bladder), and here they are particularly difficult to treat. Diets are now available that prevent the occurrence of oxalate, and if a cat has suffered one of these uroliths, then they ought to be fed.

Bladder Cancer

This is fortunately rare in the cat. Bladder cancer typically arises at one of two places. The first is in the region of urethra, the outflow to the bladder. In these cases treatment is not feasible. The other area is at the forward most portion of the bladder wall. In these cases, surgical removal of the cancer is possible, if not too much of the bladder is involved.

Blocked Urethra

Blockage of the urethra is a relatively common cause of FLUTD. It occurs almost entirely in the male cat, because the female urethra is much wider and shorter than the male one. The urethra can become blocked by one of two mechanisms: uroliths lodging within it, or more commonly, by the formation of a urethral plug.

Blockage of the urethra is an emergency. It is easily confused with constipation. Male cats straining to pass urine must be taken IMMEDIATELY to the vet.

Urethral plugs are distinct from uroliths. Urethral plugs consist of a mixture of inflammatory proteins (produced by the bladder wall), red and white blood cells, and microscopic crystals. Exactly why they form is not clear. A cat with a urethral plug may have had an episode of dysuria (difficulty passing urine), initially, but this is not always the case. What appears to be happening is the bladder wall produces inflammatory proteins than adhere to the wall of the urethra, forming a sort of glue within the urethra. Blood cells and crystals are then trapped within this glue, and the urethra becomes completely blocked.

It would not be appropriate to cover the full technique for relieving the obstruction here, but basically the cat has to be sedated or anaesthetised, and the urethral plug massaged out, or flushed back into the bladder. It may be necessary to empty the bladder by placing a needle into it through the wall of the abdomen, and then drawing off the urine with a syringe. It is usual to insert a catheter into the bladder either immediately after removing the obstruction, or as part of the process of removing the obstruction. The bladder can then be washed out using sterile saline (salty water), to remove any debris remaining in the bladder. In some cases, the catheter has to be left in place for up to several days.

In a very small proportion of cases, it may even be necessary to amputate the penis to restore a functional bladder outflow. Although a cat treated in such a way is more prone to bladder infections, most do extremely well after this procedure.

After the obstruction has been relieved, there is a period of time during which the kidney produces far more urine than normal. Most cats are extremely ill at this time. It is vital that intravenous fluids are given, possibly for several days, while the cat recovers. Hospitalisation is essential during this time.

Idiopathic FLUTD.

This is by far the most common form of FLUTD, and accounts for about two thirds of all cases. This is almost by definition, a diagnosis of exclusion. That means that if there is nothing that can be pinpointed as the cause, then it must be idiopathic! Of course, just because we do not know what causes it, does not mean that there is no cause. Hopefully research will shed more light on this topic. Possibly because we are unable to determine the cause, idiopathic FLUTD is the most frustrating of all the different types of FLUTD to treat, (with the possible exception of bladder cancer). Basically, there is no one drug or treatment that will reliably improve a cat’s condition.

Many different drugs have been used to treat idiopathic FLUTD, such as antibiotics, anti-inflammatories (e.g. steroids such as prednisolone), and the muscle relaxant propantheline. None of these drugs have been shown to be of benefit. Part of the problem with assessing drugs to treat this condition is that the vast majority of cats will get better regardless within a few days. In many ways, treatment is aimed at investigating the cat to ensure that she does not have one of the other, possibly treatable, causes outlined above. Special diets are frequently advocated, and some have been shown to reduce the incidence of FLUTD (notably Hill’s® Feline c/d cans).This disease can be very recurrent, and is distressing to cat, owner, and vet.

Bearing this in mind, the goal of treatment is not to stop the disease when it is occurring, but to prevent it from coming back in those that suffer repeated, frequent attacks. One drug that has been shown to help with this, at least in a proportion of cases is called amitryptiline. This is a drug used as an antidepressant, as well as for the treatment of cystitis in humans. It does not have a licence for use in cats in the U.K. Amytriptiline can cause sedation, although serious side effects are very rare.

If we reconsider the risk factors for the development of FLUTD, there are practical things that you can do to help prevent recurrence:

Control obesity. There are many excuses as to why animals are fat. Certainly neutering increases the tendency to become fat, but the only reason that cats are fat is that they eat too much. This is often through years of overfeeding, possibly by only a small amount. This cannot be stressed enough. Don’t delude yourself if you think your fat cat is fat for any other reason. Feed her less! Here are some tips to help your cat lose weight:

- Stop all tit-bits, table scraps and the like, then reduce the amount of cat food you give the cat by a half.

- Enrol your cat in our weight reduction clinic.

The first approach here is the cheapest, but unfortunately experience shows that few cats successfully lose weight. The second approach, where we take control of your cat’s feeding, is often very successful. The weight reduction clinic involves bringing your cat for a “weigh in” every 2 weeks or so, and feeding prescription diet designed specifically to help cats lose weight. Apart from the increased chances of success, it is preferable for other reasons as well. Cat food manufacturers incorporate vitamins and minerals according to how much food they think a cat of a given weight will eat. If you feed significantly less than that, (which is what we’re recommending), then theoretically at least, the cat could become deficient in certain nutrients. The prescription diets that we use take this into account, and the risks are eliminated. This sort of prescription diet is very different from the crystal-dissolving type commonly used to treat FLUTD.

Encourage the cat to drink more. This is not as difficult as it sounds. Simply feeding canned food will increase the amount of water that a cat consumes, even though it will physically drink more while taking dry food. You can even try mixing small amounts of water through the food. Many cats prefer to drink from dripping taps, so leaving a tap dripping slowly may help also.

Encourage the cat to exercise. If the cat likes to go outdoors, let her. It may be that outdoor cats urinate more frequently, or are less obese, but quite simply cats that have access to outdoors are less likely to develop FLUTD than those confined indoors.

Restrict meal times. Cats that are fed very frequently are more likely to develop FLUTD than cats with restricted meal times, no matter what type of diet is being fed. Although many cats like to eat very small amounts through the day (and night), it is possible to train your cat to eat at specific meal times. Put the food down in the morning, and take it way 30 minutes later. Do the same thing in the evening. At first, your cat may be upset at this, but as time goes on, she should become used to the routine.

Encourage the cat to empty her bladder more frequently. Some cats are very fussy about where and under what circumstances they will empty their bladder. For instance, many will simply not use a litter tray that has already been used. So, it is important to clean litter trays that have been used immediately. It is also a good idea to put out several litter trays around the house. In these conditions, even if the cat is left alone most of the day, there will always be a clean litter tray available.

Outlook for Affected Cats

Just as FLUTD is a generic term for a whole range of different diseases that have similar symptoms, so the outlook for an affected cat depends heavily on the exact cause of the problem. In the case of idiopathic FLUTD, this is a very frustrating disease to treat. The good news is that the cat will more than likely get better completely, without any treatment in a few days. It is distressing for the cat while it is happening, and unfortunately, there is little that can be done to affect the course of the disease. This is also irregularly recurrent. This means the cat may have another attack next week, next month, next year, or never again. There is simply no way of predicting this. There is no doubt though that in some cats the problem does keep recurring quite frequently, and it is these that may benefit from amitryptiline. If you have a male cat with FLUTD, it is vital that you monitor him carefully for signs of a blocked urethra.

Bacterial infections of the bladder carry a very good outlook. Five days treatment with an appropriate antibiotic, as determined by culture of the urine should cure the cat. Despite this, she may well develop idiopathic FLUTD sometime later.

Urolithiasis also has a good outlook in most cats. Nevertheless, in cases where the urethra is blocked, the cat’s life is seriously endangered. Severe, irreversible kidney damage can result, and several days of hospitalisation and intensive treatment my be required. However, even with the best care, some cats will die with this condition.

Bladder cancer has a poor outlook. Most of the cancers are malignant, which means they can spread to other parts of the body. If the tumour is to be removed, it has to be in an appropriate position, which means not near the outflow, and small enough so that once removed, the cat still has a functional bladder. These conditions are frequently not met, but in those that are suitable candidates for surgery, treatment is very rewarding for all concerned. If the cat has an inoperable tumour, then euthanasia may be the only treatment option. It is only necessary to euthanase affected cats if their quality of life is suffering. Certainly if they are in pain and distress every time they empty their bladder, then this is the case. However, simply having blood in the urine is not a cause for euthanasia.

HAVE A QUESTION OR WANT TO FIND US Click here